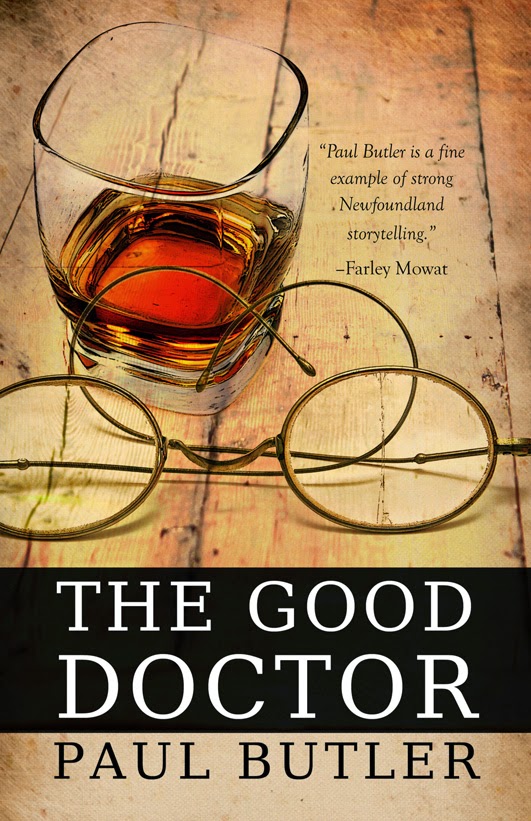

The Good Doctor

One

of Newfoundland’s finest scribes is back with The Good Doctor, the story of a journalist who unravels a 1940s medical

mystery. Recently we spoke up with author Paul Butler about his latest effort.

What inspired you to write this book?

I’d say one of the prime motivators for me in writing The Good Doctor is an instinctive mistrust of heroes ― or of historical characters who are portrayed as heroes in our culture. Wilfred Grenfell, the medical missionary who came to Newfoundland (from England) in 1892 is one of Newfoundland and Labrador’s most conspicuous “heroes”. His statue stands close-by the legislature in St. John’s. One of the main health authorities is named after him and one of the campuses of the university is named after him. One thing that became very obvious during the early reading for this project was the degree to which Grenfell himself engineered his own rise to fame, creating – quite deliberately, it seemed – an enduring iconography around himself. At the time he represented, among other things, the triumph his own race, his own class, and his own brand of Christianity. And the really curious thing about him was how much everything in his story falls into the distant background. Most people remember the Adrift on an Ice Pan episode. (In the account he published in 1909 he tells how he became trapped upon an ice floe on the way to a seriously ill patient and kept himself alive by stabbing three of his dogs and using their hides for warmth. He was rescued after a day and a night on the ice.) Much fewer people remember what happened to the patient. As a writer and dramatist, I found Grenfell’s combination of religious zeal and cultural narcissism very difficult to resist and I felt I had to explore his motivating forces, to see it both in late-Victorian terms of assumed superiority and in very modern terms of ‘celebrity branding’.

Did it come together quickly or did you really need to work at it?

From beginning to end it probably took about 4 or 5 years. Of course, this wasn’t all I was working on, but it was a complex kind of story which I envisioned as Grenfell himself and an imposter pretending to be Grenfell. The imposter shadows Grenfell though his whole career from the hospital wards in the East End of London in the 1880s, when both were medical students, to the fundraising lecture circuit in New England in the early decades of the twentieth century. I wanted to explore the themes of the missionary impulse and the sense that the missionary is someone who presents a mask to the world, who is by definition a kind of imposter.

I’d say one of the prime motivators for me in writing The Good Doctor is an instinctive mistrust of heroes ― or of historical characters who are portrayed as heroes in our culture. Wilfred Grenfell, the medical missionary who came to Newfoundland (from England) in 1892 is one of Newfoundland and Labrador’s most conspicuous “heroes”. His statue stands close-by the legislature in St. John’s. One of the main health authorities is named after him and one of the campuses of the university is named after him. One thing that became very obvious during the early reading for this project was the degree to which Grenfell himself engineered his own rise to fame, creating – quite deliberately, it seemed – an enduring iconography around himself. At the time he represented, among other things, the triumph his own race, his own class, and his own brand of Christianity. And the really curious thing about him was how much everything in his story falls into the distant background. Most people remember the Adrift on an Ice Pan episode. (In the account he published in 1909 he tells how he became trapped upon an ice floe on the way to a seriously ill patient and kept himself alive by stabbing three of his dogs and using their hides for warmth. He was rescued after a day and a night on the ice.) Much fewer people remember what happened to the patient. As a writer and dramatist, I found Grenfell’s combination of religious zeal and cultural narcissism very difficult to resist and I felt I had to explore his motivating forces, to see it both in late-Victorian terms of assumed superiority and in very modern terms of ‘celebrity branding’.

Did it come together quickly or did you really need to work at it?

From beginning to end it probably took about 4 or 5 years. Of course, this wasn’t all I was working on, but it was a complex kind of story which I envisioned as Grenfell himself and an imposter pretending to be Grenfell. The imposter shadows Grenfell though his whole career from the hospital wards in the East End of London in the 1880s, when both were medical students, to the fundraising lecture circuit in New England in the early decades of the twentieth century. I wanted to explore the themes of the missionary impulse and the sense that the missionary is someone who presents a mask to the world, who is by definition a kind of imposter.

What was the most challenging aspect of the process?

The most challenging aspect was the fact that I was taking a character who is still widely revered and I was being both critical and playful with his perceived legacy.

How far can you fictionalize and criticize a real character?

I think this depends largely on the range a real character’s impact upon the culture. If their sphere of influence goes well beyond their private life, if they have become, in effect, a politician ― someone who seeks to control or influence, or imposes their own set of values ― then I think you have a much wider licence than with someone who has become famous by coincidence or by accidental proximity to a historical event. Grenfell wasn’t merely a doctor. He was a social reformer and magistrate who imposed his own views on liquor, prayer, and society. One thing that helps particularly with Grenfell is that his own story (often in his own published words) is so very well established. Although it may add to the challenge, this stature in people’s eyes also sets the writer free. There is nothing fragile about his legacy, nothing you can easily damage. And I think the fiction writer also has a responsibility not to treat real life historical characters of influence with kid gloves. It’s impossible to treat the historical themes or potential insights seriously if you do. If you were to treat a missionary as a saint, for instance, you would miss the scars left by colonial attitudes.

What was the most rewarding part of the experience?

When I got over all the issues – ethical and otherwise – above, I really enjoyed writing this novel. It was quite a wild ride. The imposter doctor is a wonderfully rash character and the nurse (Nurse Mills) he is in love with became very much more complex as I went along. It seemed that the three of them – Grenfell, the imposter, and Nurse Mills – were each a different kind of missionary. Each of them was trying to “do good,” to heal the world around them, and I enjoyed being in their company, seeing what they would do next.

What did you learn during the process?

I had a lot of time to think about people with a burning vocation. The need to be needed is one of the most profound, and certainly one of the most enduring, desires.

How did you feel when the book was completed? I had a certain amount of trepidation ― actually a little fear, and it’s been a long time since I’ve wondered whether I really want to see a book of mine on the shelves or not, but I’m also pretty happy with the novel, happy enough to take the blows gladly if and when they come.

What has the response been like so far from those that have read it?

The response has been really good so far. I couldn’t really have hoped for better. I imagine that some people are going to take issue, which is expected, but I haven’t come across it yet.

Is your

creative process more 'inspirational' or 'perspirational'?

Both, at different times. I think the inspiration part comes when I’m not actually at the computer but when an idea comes when I’ve hardly been thinking of it.

Both, at different times. I think the inspiration part comes when I’m not actually at the computer but when an idea comes when I’ve hardly been thinking of it.

What makes a good book?

I think a good work of fiction has to take risks, has to be not too concerned with pleasing. From a writer’s point of view there may be a moment when you say to yourself ‘no, I can’t do that, I just can’t’ but that’s usually a signal that you should listen to the voice which says ‘why not?’ That second voice is the one which is interested in creativity.

What are your thoughts on Atlantic Canada's literary scene?

I’m always amazed by how lively the literary scene is in this region and how hard it is to keep up with all the exciting things people are doing. It’s difficult to imagine a better place to be a writer.

What's next on your creative agenda?

I have been working on a novel which deals with the winter of 1817-18, the coldest on record in the region. St. John’s Harbour was frozen over. Supplies could not come in and messages could not get out. Fires had destroyed much of the winter stores and the Newfoundland Governor, Francis Pickmore, became the first governor to overwinter on the island, which he did with some reluctance as gangs of starving people were roaming the streets at night setting fresh fires and looting the remaining stores. So it’s the story of a city under siege, internally, and the desperation of a winter that won’t end.

http://paulbutlernovelist.wordpress.com/